Tags

"Prufrock Moment", American literary Canon, Anti-Semitism, Apocalypse Now, Christopher Hitchens, How Unpleasant to Meet Mr. Eliot, Individual Will, integrity, Literature, Marlon Brando, Martin Sheen, Poetry, T.S. Eliot, The Hollow Men, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, time, Unacknowledged Legislation: Writer’s in the Public Sphere

Finding dirty coffee spoons is usually a sign that I need to do the dishes, that Sisyphean task that reminds me day by day that I am a weenie. I could tell my wife and brother-in-law to please stop leaving spoons and cups in the fold-out shelf in the couch, but they might remind me that they pay for the Internet and Netflix, or they may remind me that I know less about computers than they do, or else they might roll their eyes at me and make me feel inferior and so I usually just pick up the cups and spoons and wash the dishes in quiet desperation for a spinal column.

This self-denigration reminds me that I recently committed myself to the annual task of reading The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. For the record annual and anniversary means “once a year” so when your friend complains that their boyfriend forgot their four-month anniversary you might smack them upside the head for denigrating the Latin language, though that may in turn cause you to lose your friends. I discovered T. S. Eliot when I was a teenager who didn’t bath much and then wondered why girls weren’t interested in me. I knew that I wanted to be a writer, and while many of my friends would offer me contemporary science fiction novels and the novelizations of Halo fan-fiction, I was always far more interested in the Classics. The aura that surrounded the authors we spoke about in class fascinated me and I had yet to realize that men like Byron, Pound, Chaucer, and Shakespeare as men could be bawdy or obscene. My attitude was, principally, grown up teachers seem to think these guys matter, let’s find out why.

I discovered Eliot through Apocalypse Now. In case the reader doesn’t know, the film is a reimagining of Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness set during the Vietnam War. Martin Sheen is sent to kill Colonel Kurtz, an AWOL military commander who has begun a spree of killings. Sheen eventually finds the man and is held prisoner by Kurtz and near  the end of the film is a small scene in which Kurtz, played by then plump Marlon Brando, reads The Hollow Men. The perfect combination of poetics and macabre matched my teenage angst creating this beautiful and pathetic adoration of Eliot as the kind of guy who “got it.” It’s a glorious tragedy that I discovered the Modernists first, but as I’ve aged my appreciation for their work is less angst than it is actual intellectual enjoyment.

the end of the film is a small scene in which Kurtz, played by then plump Marlon Brando, reads The Hollow Men. The perfect combination of poetics and macabre matched my teenage angst creating this beautiful and pathetic adoration of Eliot as the kind of guy who “got it.” It’s a glorious tragedy that I discovered the Modernists first, but as I’ve aged my appreciation for their work is less angst than it is actual intellectual enjoyment.

I eventually bought a small Signet Classics collection of Eliot’s poems that included Preludes, The Boston Evening Transcript, The Waste Land (that grand epic that I’m pretty sure means something), and The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. I have read this poem at least once a year, every year, since the tenth grade and it’s only been in the last three years that I’ve finally figured out the damn thing, or at least come to as close an understanding as you can with a modernist poem.

It begins:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question …

Oh, do not ask, “What is it?”

Let us go and make our visit.

Many may be groaning as they remember a fat man wearing a sweater vest and a comb-over insisting that their interpretation of the poem is wrong. Before the reader believes I’m going to side with Mr. Putnathan (yes that was actually his name) they may be surprised to learn that I despise this method of analyzing and interpreting poetry. While there is certainly only one dramatic situation in any poem, the idea that The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock offers only one lesson to the reader is the malarkey that causes people to hate literature in the first place. I can’t argue that there is one interpretation because each person brings something new to the poem. All I can offer instead is my own impression and hope that the reader finds something different and leaves a comment, even if it’s a cheap ad hominem attack about my beard.

The most important line in the previous section is, “To lead you to an overwhelming question,” because that is where Prufrock as a character has been settled upon. The  dominant interpretation is that Prufrock is in love with a woman as well as being part of the upper class that he finds, not morally questionable, just suspect. Having attended a private school filled with the children of rich doctors, lawyers, politicians, engineers, and Oil businessmen I can certainly understand this revulsion, though it’s not this side of the interpretation I would like to pursue. This “overwhelming question” has bothered me since my first reading and looking at the later stanza when Prufrock says,

dominant interpretation is that Prufrock is in love with a woman as well as being part of the upper class that he finds, not morally questionable, just suspect. Having attended a private school filled with the children of rich doctors, lawyers, politicians, engineers, and Oil businessmen I can certainly understand this revulsion, though it’s not this side of the interpretation I would like to pursue. This “overwhelming question” has bothered me since my first reading and looking at the later stanza when Prufrock says,

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker,

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

It’s become clear with every new reading that Prufrock is a man everyone can sympathize with on some level, and at the same time despise because ultimately Prufrock was a man  facing a challenge who bawked and let an opportunity for personal strength pass him by.

facing a challenge who bawked and let an opportunity for personal strength pass him by.

I know this pain because I have suffered through it. A few years back I was sitting in a classroom, half an hour before the class actually started, because I prefer to be early. It’s not brown-nosing on my part, I just prefer to arrive before class starts, get some reading done, and prepare myself mentally for class. At the time I was taking a U.S. History 1301 course to satisfy my core, and while I’m an English major, history has always been one of my favorite subjects. However, my joy for the class was being stunted by a malcontent. There was a man sitting three seats behind me who, every morning would arrive fifteen minutes early and want to talk, particular about how he felt his money was being spent on bullshit programs like art, music, and the humanities. I did my best to counter his arguments by reminding him that he was attending a university and not a technical institute, but my points either weren’t registered or he couldn’t be bothered with them. Finally another young man joined us one morning and the topic of the President came up. I’m used to certain opinions about Barack Obama living in this area, but during the conversation the man said, “I don’t have a problem with black people, I just can’t stand niggers.”

I saw the moment of my greatness flicker as I sat in a stunned silence not sure how to move forward. The man shrugged and continued the talk until three more students came in, one of them African American at which point the conversation was conveniently dropped. I saw the Greatness of my opportunity to call the man out, and instead I sat in silence.

Eliot’s poem is about such moments, for not long after this first stanza he writes:

And indeed there will be time

For the yellow smoke that slides along the street,

Rubbing its back upon the window-panes;

There will be time, there will be time

To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet;

There will be time to murder and create,

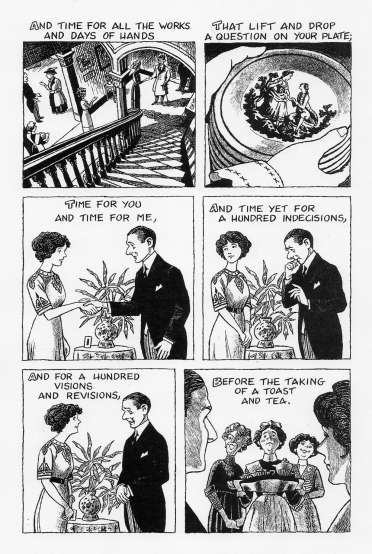

And time for all the works and days of hands

That lift and drop a question on your plate;

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions,

Before the taking of a toast and tea.

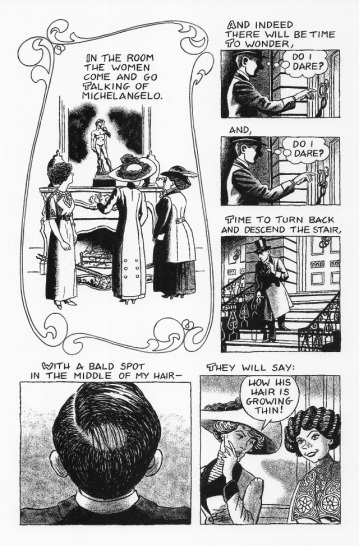

In the room the women come and go

Talking of Michelangelo.

And indeed there will be time

To wonder, “Do I dare?” and, “Do I dare?”

Time to turn back and descend the stair,

With a bald spot in the middle of my hair —

(They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”)

My morning coat, my collar mounting firmly to the chin,

My necktie rich and modest, but asserted by a simple pin —

(They will say: “But how his arms and legs are thin!”)

Do I dare

Disturb the universe?

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

The desire for comfort and stability is innate to the human species. While social philosophers and political idealists argue that human beings are innately selfish, good, evil, cruel, etc., my own experience has taught me that human beings generally are none of these. In fact the trait shared by 99% of the human population is a simple desire to live in comfort and not be bothered by the calamity of political or social strife, and so what is often lost on the casual reader of Prufrock is the damned question that keeps popping up that never gets answered: “Do I dare/Disturb the Universe?”

It’s a fair question to ask given the reality of human nature just observed. The reason  many people would identify with Prufrock, assuming they possess a love for Modernist poetry which I know they don’t, is because like my own chance, opportunities to correct or challenge ignorant or repulsive behavior are stymied because we don’t want to start fights. Fights and arguments make everyone uncomfortable, and asking inconvenient questions tends to make people less likely to like us. And we like being liked.

many people would identify with Prufrock, assuming they possess a love for Modernist poetry which I know they don’t, is because like my own chance, opportunities to correct or challenge ignorant or repulsive behavior are stymied because we don’t want to start fights. Fights and arguments make everyone uncomfortable, and asking inconvenient questions tends to make people less likely to like us. And we like being liked.

Conversations are swallowed by bitter coffee with too little creamer, and the lingering bite of “revisions” that you might have said last longer than the conversation would have most likely taken.

Being a young writer is often being a young plagiarist for that line “Talking of Michelangelo” was often buzzing around in my brain. It reeked of genius because, after all, that’s who Eliot was. He was published, he was English (or so I thought), and every word he wrote was carefully selected by his brilliant mind.

My what an idealist I was.

For the record Eliot was not English, originally. Thomas Sterns Eliot was actually born in St. Louis Missouri (I wonder if he grew up where they call it Missouruh) and eventually moved to England eventually acquiring dual citizenship. It’s amusing to note that many of Eliot’s friends teased the man behind his back because he apparently developed an “English accent” that wasn’t foolin anybody. While there he would encounter many in the literary establishment such as Virginia Wolf, James Joyce, George Orwell, and Ezra Pound. This last individual is important for being, essentially, the father of modernism, as well as possessing a similar political and philosophical penchant as Eliot.

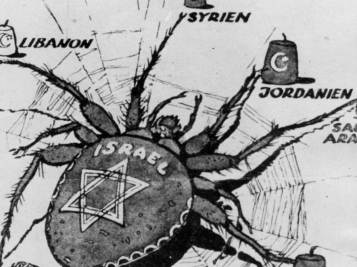

Christopher Hitchens noted this in an article published for The Nation titled How Unpleasant to Meet Mr. Eliot, it was also later published in Unacknowledged Legislation: Writer’s in the Public Sphere which I quote from here, and the first paragraph really says it all:

Was T.S. Eliot an anti-Semite? What a question! Of course he was an anti-Semite, if the terms retains any of its meaning. He was a public supporter of two political movements—the Action Francaise of Charles Maurras and the Social Credit party of Major Douglas—that identified Jews as the enemy of civilization. His magazine of high culture, the Criterion, was at best loftily indifferent to the rise of fascism. And in a famous lecture at the University of Virginia, published as after Strange Gods, he sought to identify elements of a good society and stipulated that “any large number of free-thinking Jews” was precisely what such a society did not need. (184).

Was T.S. Eliot an anti-Semite? What a question! Of course he was an anti-Semite, if the terms retains any of its meaning. He was a public supporter of two political movements—the Action Francaise of Charles Maurras and the Social Credit party of Major Douglas—that identified Jews as the enemy of civilization. His magazine of high culture, the Criterion, was at best loftily indifferent to the rise of fascism. And in a famous lecture at the University of Virginia, published as after Strange Gods, he sought to identify elements of a good society and stipulated that “any large number of free-thinking Jews” was precisely what such a society did not need. (184).

At this point the reader may object, arguing that if such is the case then I’m just wasting my time reading Eliot? What good could come of reading the man’s work? Before this review turns into character assassination Hitchens does emphasize that despite this his readers do still need to remember:

But the Julius book one, yet again, to hesitate once, hesitate twice, hesitate a hundred times before employing political standards as a device for the analysis and appreciation of poetry. (186).

Eliot’s colorful opinions about the Jews have tended to overshadow his work and allow high schoolers everywhere a solid reason not to read the man’s poetry, as if they were honestly looking for a reason though, and the end result is the universal tragedy of Prufrock is lost beneath the haze of the image of Eliot giving a Hitler a handjob while French kissing Herman Goering and I dare you to get that image out of your head. You’re seeing it now aren’t you? Aren’t you?

Prufrock’s love song covers the life of a man who had “time” to ask a question and didn’t, and in the ending stanzas the man’s bitter monologue develops into what stands as the most beautiful summation of a wasted life:

And the afternoon, the evening, sleeps so peacefully!

Smoothed by long fingers,

Asleep … tired … or it malingers,

Stretched on the floor, here beside you and me.

Should I, after tea and cakes and ices,

Have the strength to force the moment to its crisis?

But though I have wept and fasted, wept and prayed,

Though I have seen my head (grown slightly bald) brought in upon a platter,

I am no prophet — and here’s no great matter;

I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker,

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat, and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

And would it have been worth it, after all,

After the cups, the marmalade, the tea,

Among the porcelain, among some talk of you and me,

Would it have been worth while,

To have bitten off the matter with a smile,

To have squeezed the universe into a ball

To roll it towards some overwhelming question,

To say: “I am Lazarus, come from the dead,

Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all”—

If one, settling a pillow by her head

Should say: “That is not what I meant at all;

That is not it, at all.”

And would it have been worth it, after all,

Would it have been worth while,

After the sunsets and the dooryards and the sprinkled streets,

After the novels, after the teacups, after the skirts that trail along the floor—

And this, and so much more?—

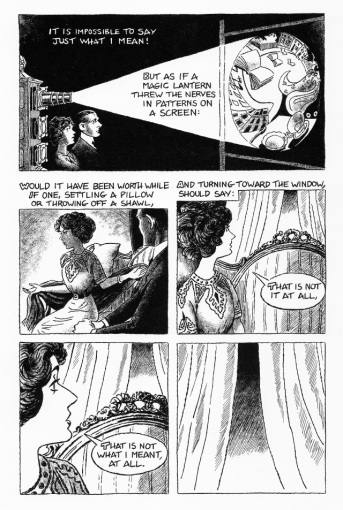

It is impossible to say just what I mean!

But as if a magic lantern threw the nerves in patterns on a screen:

Would it have been worth while

If one, settling a pillow or throwing off a shawl,

And turning toward the window, should say:

“That is not it at all,

That is not what I meant, at all.”

The poems ends with Prufrock recognizing that he shall never be a great man, nor shall he be remembered in any form or capacity. His unwillingness to stand up and speak is  ultimately his undoing, and while he may not suffer the lash or legal penalty for his fear, the ultimate punishment is recognition that he failed. This is the stuff that makes Prufrock the poem that every human being can take some lesson from, for ultimately many of us sink into that state of desperation where we are left counting our mistakes because we lacked the courage to stand up and either protest or ask the question.

ultimately his undoing, and while he may not suffer the lash or legal penalty for his fear, the ultimate punishment is recognition that he failed. This is the stuff that makes Prufrock the poem that every human being can take some lesson from, for ultimately many of us sink into that state of desperation where we are left counting our mistakes because we lacked the courage to stand up and either protest or ask the question.

The man in my U.S. history class continued to pester me with conversations up until about midway through the semester. My professor was discussing economics in the pre-Civil War period while also managing to discuss religious attitudes during the period. He began asking the students questions, working under the principle that every person in the room was a Christian, about the way they worshiped so that he could demonstrate the difference in paradigms. He picked me, and asked me my worship patterns and without hesitation I admitted, “I don’t worship I’m an atheist.” What followed was a general silence and I was informed a year later, for this admission apparently impressed him and we’ve become good friends since, that when I had spoken this every student’s sitting behind or around me widened their eyes or their jaws dropped. Let the reader understand, this was not a defiant act, nor was it an act of bravery. It was  just honest admission about myself.

just honest admission about myself.

Whatever the case the man in question never bothered me again.

Moments of greatness are actually only moments of integrity. They are moments when we are asked to specify or declare openly our beliefs or commitment, or at times to negate them because they have changed from what they were. When they appear they are not set to musical scores, nor are they often terribly dramatic, and this simplicity tends to hide their significance to our day to day reality. The chances to ask a question or admit something about myself have now often become my “Prufrock moments” because they are the decisions that I know will follow me long after they are gone. A “Prufrock moment” is an opportunity to hold your integrity.

Just as important to recognize is the fact that Prufrock is a lesson in mortality:

And indeed there will be time

To wonder, “Do I dare?” and, “Do I dare?”

Time to turn back and descend the stair,

With a bald spot in the middle of my hair —

(They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”)

My morning coat, my collar mounting firmly to the chin,

My necktie rich and modest, but asserted by a simple pin —

(They will say: “But how his arms and legs are thin!”)

Do I dare

Disturb the universe?

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

The path to mediocrity and failure is paved with the assurances that “there will be time.” There’s time to call that boy and tell him what’s in your heart and time enough to wonder if he’s really gay too, and there’s time to think about what you will say to him when you finally ride over to his place to ask him out to a movie and there’s time enough to plan and plan until you arrive at school the next day and discover someone else has already asked.

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock is a Modernist dramatic monologue that reminds the reader that “prophet’s” and “mermaids” sing only songs for those that have heart and are willing to take action.

So, moral of the story: ask that fucking guy out on a date, because the worst thing that can happen is that he says no, in which case Jimmy in Chemistry, you know the one with abs and a Jeep Cherokee, is still willing to go out with you man.

Live your life, because there won’t be time, and the universe won’t mind being disturbed.

*Writer’s Note*

Below are links to the full poem as well as an actual recording of Eliot reading The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Please enjoy.

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poem/173476

**Writer’s Second Note**

If I believed that my answer were to a person who should ever return

to the world, this flame would stand without further movement;

but since never one returns alive from this deep, if I hear true,

I answer you without fear of infamy.

-Canto 27, Inferno

This is a translation of the opening epigram of Eliot’s poem and it only lends more credence to the idea that life is about taking chances and not resting quietly in desperation.

**Writer’s Third Note**

The reader probably observed the use of comics to provide context for the poem. While arranging this article I stumbled upon a blog operated by a man name of Julian Peters who produces comics about the great works of literature. These images come from his interpretation of the poem. If the reader is interested in reading his entire production of the poem they can follow the link below:

***Writer’s FOURTH Note***

Below are a few articles and facts about Eliot including a link to the Hitchens essay as well as an interesting article about Eliot writing to Groucho Marx of the Marx Brothers. Where was THAT lesson in high school, I mean, right?

Facts about Eliot, Hitchens’s Review, and an article about T.S. Eliot and Groucho Marx

http://s3.amazonaws.com/thenation/pdf/9608017574.pdf

http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-fraught-friendship-of-t-s-eliot-and-groucho-marx

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jan/10/from-tom-to-ts-eliot-world-poet

http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4738/the-art-of-poetry-no-1-t-s-eliot